How Does Cystic Fibrosis Develop?

Reviewed by: HU Medical Review Board | Last reviewed: September 2019 | Last updated: June 2021

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetically inherited disease that affects one protein in the body. In turn, this mutated protein causes the body to create thick, sticky mucus that clogs virtually the entire body, but especially the lungs and pancreas. Cause of death for the vast majority of people with CF is advanced lung disease.

How is cystic fibrosis inherited?

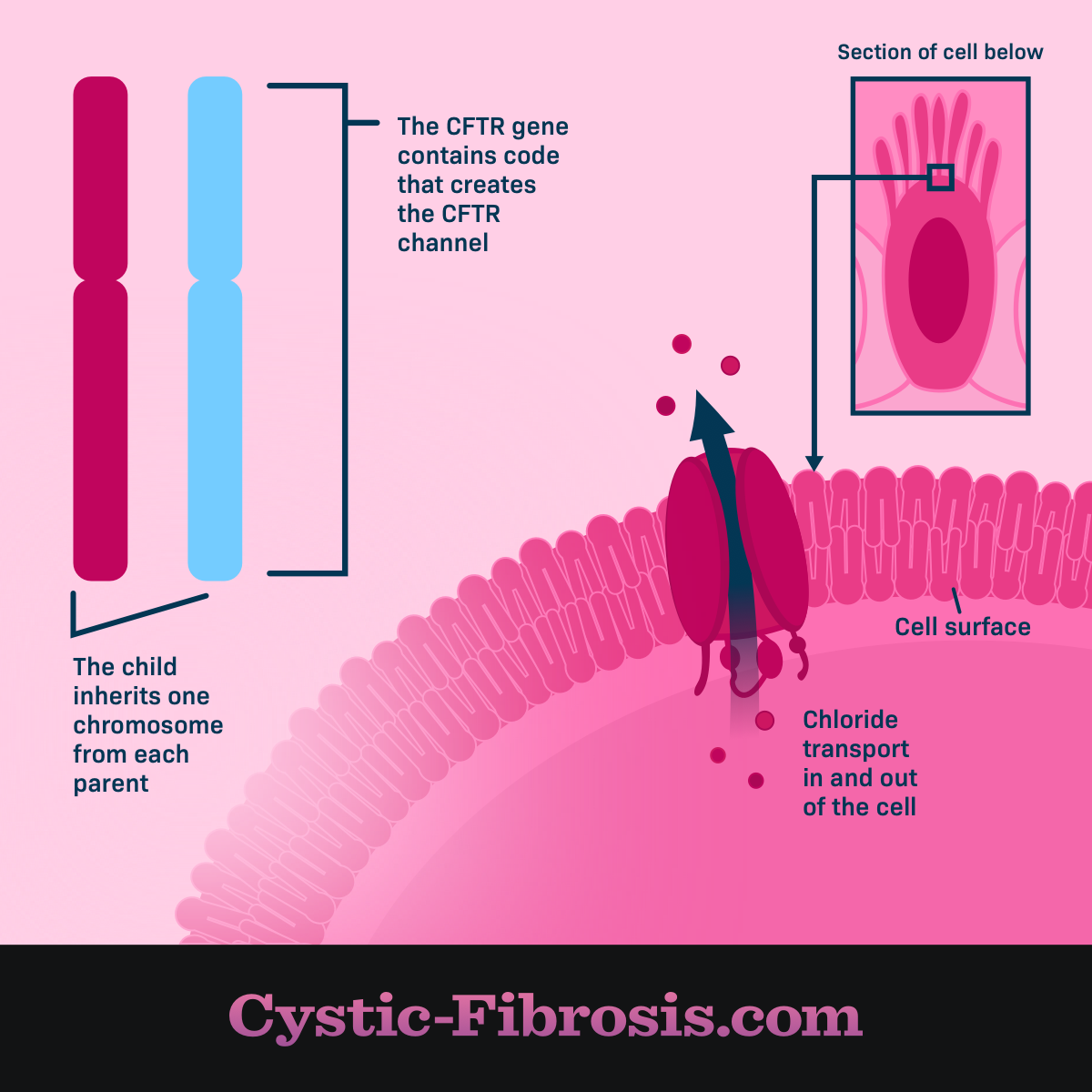

CF is what is known as an autosomal recessive genetic disorder, meaning that the person with CF inherited two copies of a defective gene -- one copy from each parent. This mutated gene, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, is located on the long arm (q) of chromosome 7 (7q31.2).1,2 Unlike some other genetic conditions, cystic fibrosis is equally prevalent in males and females. While the prevalence of CF is the same in both men and women, the severity of CF symptoms can vary in men and women.

People with only one copy of the defective CF gene are called carriers. Carriers do not develop CF because they have a dominant gene that causes their CFTR protein to be handled correctly in the body. CF is the most common life-limiting genetic disorder.3

What does CFTR mean?

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator or CFTR describes what this protein does in the body. CF stands for cystic fibrosis, which refers to the organ scarring that takes place over time. Transmembrane describes how the protein moves from one side of a cell membrane to the other. Specifically, the CFTR protein carries the chloride (Cl) ion across a cell membrane. Conductance means that things like ions are let through the cell membrane. Regulator means that something is controlled as it moves through a cell membrane.

Why does this gene cause cystic fibrosis?

The CFTR gene is responsible for giving the body instructions on how to handle the CFTR protein. A normal CFTR protein is made of 1,480 amino acids and folds into a stable 3-D shape that carries chloride across the cell membrane. Mutated CFTR proteins throw off the balance of chloride and water at the cell surface, resulting in thick, sticky mucus.

The CFTR protein is located in the exocrine system. The exocrine system includes every organ of the body that makes mucus, including the lungs, liver, pancreas, and intestines, sinuses, and sex organs.1

Figure 1. CF chromosome that contains CFTR gene that causes chloride to cross the cell membraine

Classes of CFTR mutations

Scientists have identified at least 1,700 genetic mutations that cause CF. Some mutations cause virtually no CFTR function and others create at least some function. These mutations are grouped into six classes.3-5

CFTR Mutations3-5

| Type of mutation | Type of CFTR defect | Percent of people with CF who have at least 1 mutations |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | CFTR protein is created and moves to the cell surface, allowing the transfer of chloride and water. | |

| Class I | No functional CFTR protein is created. | 22 percent |

| Class II | CFTR protein is created but misfolds, keeping it from moving to the cell surface. This is called a trafficking defect. | 88 percent |

| Class III | CFTR protein is created and moves to the cell surface but the channel gate does not open. This is called a defective channel regulation. | 6 percent |

| Class IV | CFTR protein is created and moves to the cell surface but the channel function is faulty. This is called decreased channel conductance. | 6 percent |

| Class V | Normal CFTR protein is created and moves correctly to the cell surface but not enough. This is called reduced synthesis of CFTR. | 5 percent |

| Class VI | CFTR protein is created but it does not work properly at the cell membrane. This is called decreased CFTR stability. | 5 percent |

The most common CFTR mutation is F508del and 85. 8 percent of individuals in the CF Foundation’s Patient Registry have at least one copy of this mutation. F508del is a Class II mutation.4

The latest medications, CFTR modulators, target specific genetic mutations by fixing how the CFTR protein or the cell membrane works.

Differences among classes

Scientists have identified differences in the health and response to treatment among the different classes of CF mutations.

Most people with CF fall into Class I-III. People with these mutations tend to be younger, are more likely to be prescribed pancreatic enzymes, to develop CF-related diabetes and liver disease, and have acid reflux.4 Class I-III mutations are considered more severe forms of CF because there is no residual CFTR function.3

Class IV-VI mutations are more common for those under age 10 and those who are 50 and older. People with these CFTR mutations have milder lung disease and some pancreatic function which is why they tend to live much longer than those with more severe types of CF.3 They are also more likely to develop pancreatitis and osteoporosis.4

Genotype versus phenotype versus theratype

Genotype refers to the genetic code in a cell. Genotyping is the process in which a genetic mutation is identified through genetic testing. Phenotype refers to the way a genotype is expressed, such as hair color. In the case of CF, phenotype explains which symptoms are more or less severe in certain genotypes. Theratyping refers to the process of identifying a genetic mutation based on how the body responds to available therapy.4